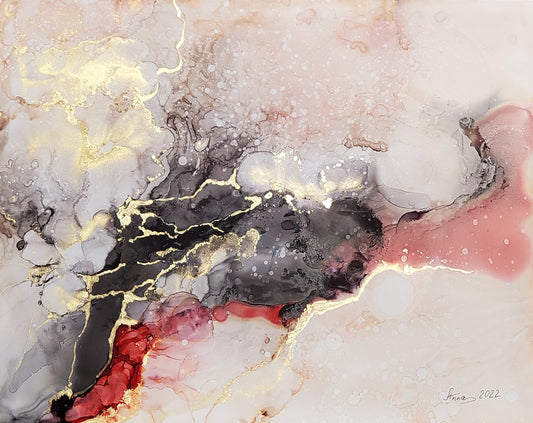

Mark Rothko, No. 14, 1960

Mark Rothko’s name is synonymous with profound emotion, spiritual inquiry, and the transformative power of art. His paintings—often monumental in scale and simple in composition—are anything but straightforward. They demand time, patience, and vulnerability, offering viewers a chance to connect with something larger than themselves. Behind these works, however, was a complex individual whose journey from modest beginnings to artistic greatness was as layered and textured as his art.

This introduction explores the life, influences, and ambitions of Rothko, laying the groundwork for understanding his philosophy, his art, and his enduring impact.

Early Life: The Immigrant Experience

Born Marcus Rothkowitz on September 25, 1903, in Dvinsk, Russia (now Daugavpils, Latvia), Rothko’s early life was marked by upheaval. At the time, his Jewish family faced persecution in a region rife with anti-Semitic violence. Rothko’s father, Jacob, a pharmacist and intellectual, decided to emigrate to the United States in search of safety and opportunity.

In 1913, at the age of 10, Rothko and his family joined Jacob in Portland, Oregon. The transition was anything but smooth. Jacob passed away shortly after the family’s arrival, leaving Rothko, his mother, and siblings to navigate life in a new and unfamiliar country. This early experience of displacement, loss, and resilience shaped Rothko’s worldview and later informed the existential themes of his art.

As a young boy, Rothko excelled academically, showing a particular talent for critical thinking and self-expression. He absorbed the liberal and socialist ideals prevalent in his immigrant community, ideals that would influence both his art and his life.

The Rothkowitz family before leaving Latvia, circa 1910. Markus Rothkowitz (Mark Rothko) is bottom left, holding the dog.

Education and the Search for Meaning

Rothko’s academic promise earned him a scholarship to Yale University in 1921. However, his time at Yale was fraught with disillusionment. He found the institution elitist and inhospitable to working-class immigrants like himself. The experience deepened his skepticism toward authority and conventional pathways to success.

After two years, Rothko left Yale without a degree and moved to New York City. Here, he discovered his true calling: art. Enrolling in classes at the Art Students League and the New School of Design, Rothko studied under influential figures like Max Weber, who introduced him to the expressive possibilities of modernism.

New York in the 1920s and 1930s was a cultural melting pot, buzzing with avant-garde ideas. Rothko immersed himself in this vibrant environment, forming connections with other emerging artists and intellectuals. During this period, his work reflected the influence of European modernists like Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and the Surrealists.

From Figurative Art to Abstraction

Rothko’s early works were largely figurative, often depicting urban scenes and portraits imbued with psychological depth. However, as he matured as an artist, he grew restless with representational forms. Influenced by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Carl Jung, and classical mythology, Rothko began to explore more universal themes.

By the 1940s, Rothko had transitioned to abstraction, co-founding the group The Ten, which sought to push the boundaries of art beyond representation. This shift was not merely aesthetic but deeply philosophical. Rothko wanted to create art that transcended the specifics of time and place, reaching for the eternal and the sublime.

His breakthrough came in the late 1940s with the development of his signature Color Field style. These large, abstract canvases, characterized by luminous blocks of color and soft-edged forms, were unlike anything the art world had seen. Rothko had found his voice—a language of pure emotion and spirituality.

The Artist as a Philosopher

Rothko viewed himself not just as a painter but as a thinker and communicator. He believed that art should address the fundamental questions of existence: Why are we here? What does it mean to be human? His work is often compared to music or poetry, forms that bypass rational thought and speak directly to the soul.

In interviews and writings, Rothko articulated his belief that art should evoke profound emotional responses. “The people who weep before my pictures,” he said, “are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” This connection between artist and audience was central to his philosophy.

Rothko’s influences were wide-ranging, from Greek tragedy and philosophy to the works of modern thinkers like Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer. These intellectual underpinnings set him apart from many of his contemporaries, grounding his work in a deep sense of purpose and inquiry.

Challenges and Triumphs

Rothko’s rise to prominence in the 1950s was accompanied by both acclaim and controversy. He became a leading figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement, alongside artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Yet, Rothko resisted being categorized, insisting that his work was not merely part of an artistic trend but a lifelong pursuit of truth and meaning.

Despite his success, Rothko struggled with the demands of fame and the commercialization of art. He was deeply protective of his work, often clashing with collectors, galleries, and critics over how it was displayed and interpreted. This tension, along with his health and personal struggles, would shape the final chapters of his life and career.

Legacy of a Visionary

Mark Rothko’s life was as layered as his paintings—marked by moments of joy, despair, triumph, and solitude. He sought to create art that was universal yet deeply personal, accessible yet profoundly complex. Through his exploration of color, form, and emotion, Rothko redefined what art could be, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire and challenge.

This book delves into the many dimensions of Rothko’s life and work, from his early struggles to his philosophical breakthroughs, and from his artistic triumphs to his enduring influence. To understand Rothko is to embark on a journey of discovery—not just of the artist but of oneself.

2. From Beginnings to Breakthrough: Rothko’s Artistic Journey

Rothko’s artistic evolution is best understood as a series of breakthroughs, each reflecting his relentless search for a visual language that could express the depth of human experience. This chapter chronicles his progression from figurative painter to one of the leading figures of Abstract Expressionism.

Early Figurative Works

Rothko’s earliest works, such as Street Scene and Subway Scene, were heavily influenced by his experiences as an immigrant in New York City. These paintings, characterized by muted tones and anonymous figures, reflected the alienation and anonymity of urban life. While rooted in realism, they hinted at Rothko’s later focus on psychological depth and the human condition.

The Mythological Period

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Rothko’s work began to reflect his fascination with mythology and existential themes. Influenced by the Surrealists and Carl Jung’s theories on the collective unconscious, Rothko explored universal archetypes and symbols. Paintings such as The Omen of the Eagle (1942) reveal his interest in creating timeless narratives through abstract forms.

During this period, Rothko co-founded the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, alongside artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Together, they sought to redefine the role of the artist as a visionary capable of transcending traditional forms and exploring new realms of emotional and spiritual expression.

Arrival at Color Field Painting

The defining breakthrough in Rothko’s career came in the late 1940s, when he developed his iconic Color Field style. Rejecting the complexity of his earlier work, Rothko began creating large-scale canvases composed of horizontal bands of color. These works, such as No. 3/No. 13 (Magenta, Black, Green on Orange) (1949), stripped away narrative and detail, leaving only the essence of visual experience.

Rothko’s Color Field paintings were revolutionary in their ability to evoke profound emotional responses. By using subtle shifts in tone and scale, he created works that seemed to radiate light and pulse with energy, enveloping viewers in a meditative space.

Challenges and Triumphs

Despite his growing acclaim, Rothko faced significant challenges throughout his career. He often struggled to reconcile his desire for artistic purity with the commercial demands of the art world. In the 1950s, his increasing prominence brought both recognition and tension, as he sought to maintain the integrity of his work in the face of widespread success.

Rothko’s journey to artistic maturity is a testament to his unwavering commitment to exploring the depths of human emotion and spiritual transcendence. His work, shaped by years of experimentation and introspection, represents a profound engagement with the mysteries of existence.

3. The Color Field: Rothko’s Visual Language

Mark Rothko’s signature style, defined by luminous fields of color, transformed the landscape of modern art. These paintings—simple in structure yet profoundly complex in effect—are not merely decorative or representational. Instead, they serve as portals to an emotional and spiritual realm, encouraging viewers to confront their inner selves.

The Structure of a Rothko Painting

A typical Rothko painting from his mature period features large, rectangular blocks of color, often set against a softly textured background. These forms hover and shift, their edges blurring as if dissolving into the surrounding space. Rothko’s compositions avoid symmetry, creating a sense of tension and movement that invites prolonged contemplation.

The artist’s use of scale was equally intentional. His paintings are monumental in size, designed to envelop the viewer. Rothko often insisted that his works be hung low on walls to create an immersive experience. He wanted his art to engage viewers physically and emotionally, drawing them into the world of the painting.

The Emotional Power of Color

Rothko’s genius lay in his ability to imbue color with emotion. His palette ranged from vibrant yellows and oranges to deep reds, blacks, and grays, each shade carefully chosen to evoke a specific mood. In works like No. 14 (1951), Rothko used warm tones to convey a sense of radiance and optimism, while later paintings, such as Untitled (Black on Gray) (1969), reflect darker, more introspective themes.

For Rothko, color was not merely a visual element but a vehicle for emotional resonance. He believed that his paintings could communicate universal experiences—joy, sorrow, awe—bypassing language and cultural barriers. His works achieve this by creating a sense of presence, as if the paintings themselves are alive with emotion.

Rothko’s Philosophy of the Viewer

Rothko often spoke of his art as a dialogue between the painting and the viewer. He believed that the viewer’s response completed the work, transforming it from an object into an experience. In his words, "A painting is not about an experience. It is an experience."

To foster this connection, Rothko demanded a specific environment for his works. He was critical of how his paintings were displayed in galleries and often expressed frustration with audiences who treated them as decorative pieces. He wanted his art to be encountered in quiet, contemplative spaces, free from distractions.

The Silence of Rothko’s Canvases

One of the most striking qualities of Rothko’s Color Field paintings is their silence. Unlike the dynamic, gestural work of contemporaries like Jackson Pollock, Rothko’s canvases exude stillness and calm. This quiet intensity invites viewers to slow down, to engage in a kind of visual meditation.

Art critic Clement Greenberg described Rothko’s work as "a kind of tragic optimism," capturing its unique ability to balance beauty with existential weight. This duality—between presence and absence, light and shadow—is central to the power of Rothko’s art.

4. The Role of Emotion in Rothko’s Work

For Mark Rothko, emotion was the essence of art. His paintings are not about narrative or representation but about creating an emotional resonance that transcends time and space. This chapter explores how Rothko used color, scale, and composition to engage viewers on a deeply personal level.

Art as a Vessel for Human Experience

Rothko’s belief in the transformative power of art stemmed from his conviction that painting should address fundamental human experiences. In a world increasingly dominated by technology and materialism, he sought to create works that reconnected people with their emotions.

"My paintings are not about the relationship of color or form," Rothko explained. "They are about the condition of the human spirit." This ethos guided every aspect of his creative process, from his choice of materials to the spatial arrangement of his canvases.

Rothko’s Use of Light and Space

Light plays a central role in Rothko’s paintings, often serving as a metaphor for emotional and spiritual illumination. By layering translucent pigments, he created works that seem to glow from within, as if lit by an internal source. This technique allows the paintings to change subtly depending on the lighting and the viewer’s position, creating a dynamic, ever-shifting experience.

Rothko’s use of space is equally intentional. The negative space in his compositions functions not as emptiness but as a presence, a silent counterpart to the blocks of color. This interplay between form and void mirrors the balance between emotion and introspection, presence and absence.

Emotional Depth in Rothko’s Later Works

Rothko’s later works, characterized by darker palettes and simpler forms, reflect a shift toward introspection and existential inquiry. These paintings, such as Black on Maroon (1958), convey a sense of gravity and finality, suggesting themes of mortality and transcendence.

Despite their somber tone, these works are not devoid of hope. Instead, they invite viewers to confront their own fears and uncertainties, offering a path toward acceptance and understanding.

5. Philosophy of the Sublime: Rothko and the Human Spirit

Mark Rothko’s art embodies the philosophy of the sublime—a concept that dates back to ancient philosophy and gained prominence during the Romantic period. The sublime, as defined by thinkers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant, is the experience of overwhelming grandeur or terror that transcends the mundane and connects us to the infinite. Rothko’s works, with their immense scale and transcendent use of color, are visual expressions of this philosophy.

Art as a Portal to the Sublime

For Rothko, art was not merely an aesthetic endeavor but a profound spiritual journey. His paintings aim to evoke awe and introspection, urging viewers to confront their deepest emotions. This aligns closely with the sublime’s focus on evoking feelings that go beyond ordinary experience. Rothko once remarked, “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom.”

By stripping his compositions of literal forms, Rothko created works that function as meditative spaces. His paintings are devoid of distractions, allowing viewers to focus entirely on their internal reactions. This engagement transforms the act of viewing into a personal encounter with the infinite.

Scale as a Tool for Transcendence

Rothko’s use of scale is integral to his philosophy. His canvases are often monumental, dwarfing the viewer and creating a sense of immersion. This deliberate manipulation of scale mirrors the Romantic sublime, where vast landscapes or towering mountains evoke feelings of insignificance and wonder.

The sheer size of Rothko’s works forces viewers to engage physically, drawing them into a space where time seems to stand still. The paintings become environments in their own right—silent, expansive, and charged with emotion.

The Relationship Between Light and Shadow

Rothko’s exploration of light and shadow further enhances the sublime qualities of his work. His paintings are often described as glowing, a result of his meticulous layering of translucent pigments. This interplay between light and dark creates a sense of depth and mystery, inviting viewers to lose themselves in the painting’s luminous spaces.

This use of light recalls the works of Romantic painters like J.M.W. Turner, who similarly sought to capture the ineffable through atmospheric effects. For Rothko, however, the light is not about depicting nature but about illuminating the soul.

The Sublime as a Human Experience

Rothko’s works are deeply human, despite their abstract nature. They are not about the external world but about the internal landscape of the viewer. His paintings ask us to reflect on our fears, hopes, and connections to the larger universe.

By engaging with Rothko’s art, viewers are invited to confront the sublime within themselves—a confrontation that is both humbling and elevating. Rothko’s commitment to this vision makes his work timeless, resonating across cultures and generations.

6. Art and Spirituality: Rothko’s Chapel as a Sanctuary

Mark Rothko’s commitment to the spiritual dimension of art reached its zenith in the Rothko Chapel, a non-denominational space in Houston, Texas. Conceived as a sanctuary for contemplation and reflection, the chapel is one of Rothko’s most profound achievements, combining his artistic vision with his belief in the transformative power of art.

The Vision Behind the Chapel

The Rothko Chapel was commissioned in the mid-1960s by philanthropists John and Dominique de Menil. Rothko was tasked with creating a space that transcended religious boundaries and provided a universal spiritual experience. This challenge aligned perfectly with Rothko’s lifelong exploration of themes like transcendence, solitude, and the sublime.

Rothko worked tirelessly on the project, producing 14 monumental paintings specifically for the space. These works, predominantly in shades of black, gray, and maroon, are stark and meditative, reflecting Rothko’s late-career focus on simplicity and depth.

A Space for Contemplation

The chapel’s design complements Rothko’s vision. The octagonal room, with its high ceilings and natural light filtered through a skylight, creates an atmosphere of quiet reverence. Visitors are encouraged to sit in silence, allowing the paintings to envelop them.

The absence of traditional religious symbols allows the space to resonate with people of all faiths—or none. It is a place where art becomes a spiritual experience, where viewers can connect with something greater than themselves.

Rothko’s Spiritual Legacy

The Rothko Chapel stands as a testament to Rothko’s belief in the power of art to address the human spirit. Its enduring impact is evident in the thousands of visitors who come each year to experience its profound stillness.

Rothko’s vision for the chapel was realized shortly before his death in 1970, making it both a culmination of his life’s work and a final statement on his artistic philosophy. It remains one of the most significant examples of art’s ability to create sacred space.

7. Darkness and Light: Rothko’s Late Period and Legacy

Mark Rothko’s later years were marked by a profound shift in his artistic output, reflecting a journey inward. His palette darkened, his forms became simpler, and his works seemed to grapple with themes of mortality, despair, and the human condition. Despite their somber tone, these late paintings remain some of his most powerful and enduring creations.

The Shift to Darkness

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Rothko’s works began to exhibit a noticeable change. Gone were the vibrant yellows, oranges, and reds of his earlier Color Field paintings. In their place came somber tones of black, gray, maroon, and muted blues.

This transition was not merely a stylistic choice but a reflection of Rothko’s evolving philosophy. He sought to strip away all but the essentials, creating works that were both minimalist and deeply emotional. These paintings, such as Black in Deep Red (1957), convey a sense of introspection and weight, asking viewers to confront their own feelings of isolation and impermanence.

The Seagram Murals: A Monument to Solitude

One of the most significant projects of Rothko’s late period was the Seagram Murals, a series of paintings originally commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York City. Rothko envisioned these works as an immersive experience, describing them as a means to create “a place” rather than a collection of artworks.

However, as the project progressed, Rothko became disillusioned with the idea of his paintings being displayed in a commercial setting. He ultimately withdrew from the commission, donating some of the murals to institutions like the Tate Gallery in London, where they remain a highlight of his legacy.

The Seagram Murals are haunting in their simplicity and depth. Their dark, imposing rectangles seem to pulsate with an almost oppressive energy, enveloping the viewer in a space of contemplation and solitude.

Themes of Mortality

Rothko’s health and mental state declined during his later years. Diagnosed with a heart condition and struggling with depression, his work took on an even greater sense of finality. The Black on Gray series, created in the final years of his life, is particularly poignant. These stark, monochromatic canvases speak to a confrontation with mortality, their simplicity emphasizing the fragility of existence.

Yet, even in these works, there is a sense of quiet resilience. Rothko’s ability to find beauty in darkness underscores his belief in art’s capacity to provide solace and meaning, even in life’s most challenging moments.

Rothko’s Influence and Legacy

Mark Rothko’s influence extends far beyond his own body of work. He is celebrated not only for his contributions to Abstract Expressionism but also for his role in redefining the purpose of art. Rothko’s insistence on emotional depth and spiritual connection has inspired generations of artists, from minimalist painters to contemporary installation artists.

Moreover, his work continues to resonate with audiences worldwide. The Rothko Chapel, the Seagram Murals, and his countless Color Field paintings remain enduring testaments to his vision. They remind us of the power of art to explore the human condition, to confront darkness, and to find light.

8. The Eternal Rothko

Mark Rothko’s art transcends its time, speaking to universal truths about emotion, existence, and the sublime. His works are not mere objects to be admired but experiences to be felt—windows into the human soul.

Rothko’s journey, from a young immigrant in Portland to a towering figure in the art world, is a testament to the power of perseverance, introspection, and vision. He sought to create works that could speak to all people, regardless of their background, and he succeeded. His paintings remind us of the profound connections we share as human beings and the transformative power of art to illuminate those connections.

In a world that often feels fragmented and chaotic, Rothko’s art offers a place of stillness and reflection. It invites us to pause, to look inward, and to find meaning in the vast, silent spaces he so masterfully created.